America's "Liberation Day": A Long Week of Tariffs

Maybe Now America will be Liberated of Tariff News

Tariffs are the big talk of this week, but I have not yet seen a great breakdown of what is supposed to happen, what will happen, and what might happen. As I believe that public policy discussion should be more accessible to non-economists and non-political scientists, I thought that it would be worthwhile to give my two cents, and try to give a primer on a bit of what is happening. I have also seen a lot of misinformation and disinformation floating around about all of this and I wanted to clear the air a bit in the current discussion.

As a Background

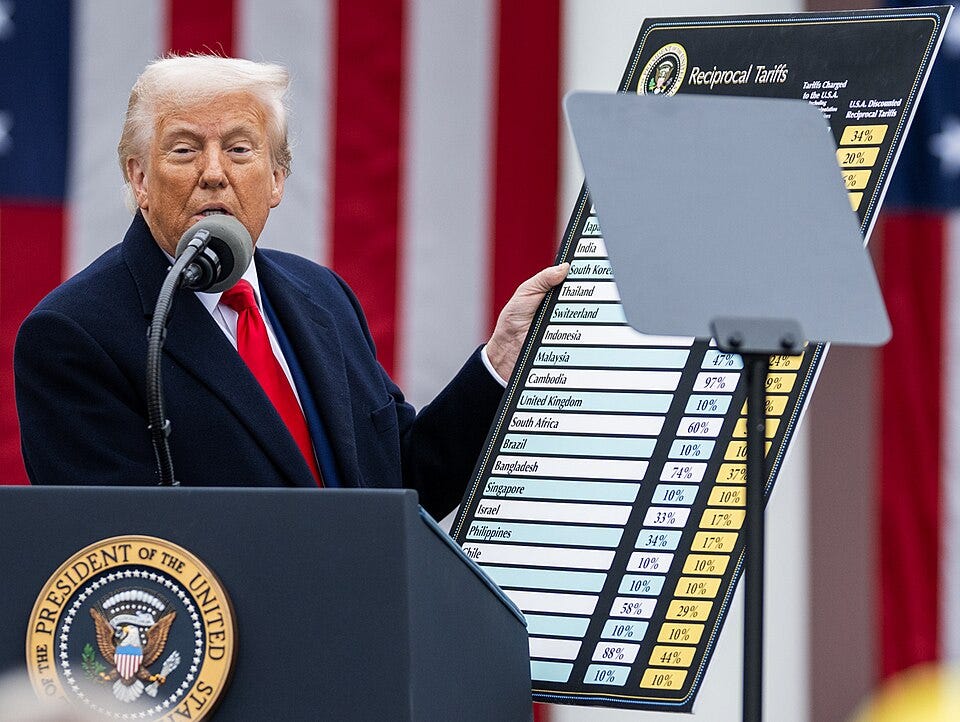

Last Wednesday, April 2nd, President Donald Trump announced a “Liberation Day” for the United States. This was the announcement via executive order of a global 10% tariff on all imported goods to commence on April 5th, with more targeted tariffs to individual countries kicking off today, April 9th. China was specifically targeted by an additional executive order, adding both flat-rate tariffs and a 34% tariff to imported Chinese goods later in May. This Chinese-exclusive tariff was amended yesterday by executive order to commence in line with other country-specific tariffs today, and to raise the percentage-based tariff to 84%. This is partially in a move to fulfill a long-standing campaign promise to enact tariffs, allegedly to correct trade deficits, and was proceeded by the announcement of tariffs on automobiles and automobile parts on March 26th.

The Trump administration seems to be variably open and closed to negotiating these tariffs with individual countries, with Vietnam being told publicly by U.S. senior trade advisor Peter Navarro stating that, “this is not a negotiation.” However President Trump himself has stated that negotiation may be possible for some countries, and may not be possible for others.

China has notably refused to back down on the tariffs. Despite being one of America’s largest trading partners, the US has imposed a 104% cumulative tariff on the country, and China has responded in turn by issuing an 84% tariff on the United States, stating that they will not back down to US pressure. Chinese leaders have been calling for world leaders to present a unified front against these tariffs.

Many authoritarian leaders are seeing this as a boon for their own countries. While this will take some time to settle out, Russian leaders, for example, have spoken out about improved outlooks both on the war in Ukraine and the viability of Russia as a trading partner. In Chinese social media, which was largely critical of President Xi Jinping in recent times, blame has as least temporarily shifted to the United States for China’s economic outlook.

In response to these tariffs, prior to today, every major domestic stock market has taken a significant hit, a “correction” in trading terminology (that is, an over 10% adjustment in value). President Trump has specifically warned auto-makers not to raise prices in response to the tariffs. Economists are trending toward viewing the economic shock as indicative of a possible recession.

As-of today, the president has announced that the global 10% tariff will remain in place, along with a further heightened Chinese tariff of 125% and the preexisting sector-specific tariffs. Notably, this would need to be passed by executive order (instead of simply declared on the president’s Truth Social page), but this was not publicly posted on the White House website until April 10th.

While ordinarily the President of the United States is unable to issue tariffs as that power is controlled by Congress, the President does have the power to do so during a declared state of emergency, via the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. This is the legal basis for the current declared tariffs.

What does this mean?

Tariffs are traditionally typically meant to boost domestic production of a good, similarly to subsidies. Subsidies work by cheapening the domestic production of a good (by kicking over a bit of money to domestic producers), while tariffs work by making foreign substitutes more expensive (by leveraging a tax on the good at the port of entry). However, subsidies are an expenditure by the government and tariffs are a tax collected by the government. Both of these are long-term solutions to any problem, as businesses must adjust to the expectations of the market. Potential entrepreneurs will only invest normally in times of stability, so as to make a stable profit.

The tariff calculations appear to have used a straightforward equation in calculating how to leverage country-specific tariffs. However, even economists associated with conservative institutions have taken significant issue over these calculations, stating that there are unquestionable mistakes. Some media outlets have particularly noted that the White House’s findings reflect those that would be created by generative AI, if prompted to create tariff policy for the United States. This is somewhat troubling, as it means either: one, that White House staffers used a tool like ChatGPT or Claude for economic policy advice instead of actual economists or two, that White House staffers are only as competent as generative AI in crafting complex policy. Generative AI cannot give the nuance required yet for something as complicated as tariff policy.

Part of the claim put forth by the White House is that these tariffs are meant to offset the national deficit and correct trade imbalances. However, because this order was put forth by the executive portion of the government and Congress still handles budgetary matters, as-of this moment, Congress cannot count on tariffs as part of the annual budget. This disconnect is evident in other areas (notably that legally, the tariffs were in full force on April 9th because the executive order was only signed to take effect on the 10th), but shows that despite possessing the legal power to push through these tariffs, it is likely not fully thought through.

Why does this matter?

To take a step back, the optics of declaring a “Liberation Day” are already quite overdramatic. The only “liberation” that can be reasonably taken away from this tariff policy is the “Golden Rule” proposed by the White House: that other countries have mistreated the American economy and that they need to be mistreated in return—almost a “liberation” of a compulsion to be nice. This goes beyond missing the point of the actual “Golden Rule,” into a direct bastardization of the concept. The point of the Golden Rule is to treat others with the respect that you yourself want, not to slight those around you based on your perceived slights. That is to say that the Golden Rule has a place in international diplomacy especially, where individual, human-to-human discussions are had; applying it to economic policy like tariffs already seems spurious, but to then redefine its very nature by flipping its paradigm seems untenable. I have more to say here (maybe for another time), but the verbiage behind this supposed “economic liberation” is both a kind of textbook reactionary populism and also dramatically overselling the present economic situation.

If the goal is to boost domestic industry (as is one of the stated goals), then dramatically increasing global tariffs all at once is not the way to accomplish this. Businesses have two things to keep track of to function: labor (the workers supporting its functions) and capital (the materials and buildings utilized to provide the good or service). Neither is easy to move; neither is straightforward to adapt. Much of what the White House is currently complaining about is tied to offshoring of domestic manufacturing, so let us first consider capital, and what it would take to return.

For capital in manufacturing to return to the States, a few things can or must happen. If these tariffs persist, it will become unreasonable for companies to continue operating with their current supply chains without changing prices. There are very few cases where nothing will change, and that will likely be akin to local farmer’s markets where the supply chain is completely local (and even then, if seeds for crops are imported, prices will go up).

Consider chocolate and coffee. Outside of extremely limited supply in Hawaii, cacao and coffee beans largely do not grow in the United States. While certainly, chocolate manufacturing could be entirely onshored (imagine more towns like Hershey, PA), there is simply no replacing the raw input at scale. That is, a 10% increase in the cost of cacao for the business will directly result in higher domestic manfacturing costs. No business will allow this to eat into their profit margins in the long-term. The business will raise their prices accordingly1. Domestic manufacturers with domestic supply chains (say, those few who are able to source from only the Hawaiian crop), if their chocolate products are already competitively priced, will raise their prices to match the going market rate2. Coffee manufacturing will suffer a similar pattern. For these products, the crops simply cannot grow throughout most of the United States. It is not that there does not currently exist a viable domestic alternative, it is that there cannot exist a viable domestic alternative without acts of science or nature, given the current demand of these products.

For labor in manufacturing to return in the States, either large-scale immigration will need to take place (very unlikely at best in the current administration, since these jobs are not the touted H1-B jobs) or valuable and meaningful manufacturing jobs will need to be overrepresented in the market, to draw domestic talent to those jobs. To that, the United States labor force does not currently possess the skillsets necessary for large-scale domestic manufacturing. Despite Treasury Secretary Bessent’s insistence that furloughed federal workers can and should help fill the gap, the skills of these specialized individuals largely do not overlap with the manufacturing sector. Even if these jobs were manufactured overnight (pun intended), it would take months to train up labor to be efficient and productive in that role. That sort of labor, despite being termed “unskilled3,” does require a healthy amount of wind-up time.

All this leads to, why would a business owner spend millions in opening a manufacturing plant domestically when it may not be staffable or productive in the short-term? And why would this same business owner bank their profitability on the stability of these tariffs when within a week of being announced, before they go into effect, they have already changed? And then changed again significantly on the day they were due to go into effect? This sort of unpredictability is not conducive to business, and this lack of confidence in the market is maybe somewhat surprisingly driving a lot of issues in the economy right now.

Economists generally agree that a trade deficit is not necessarily a bad thing. Even if a trade deficit would be solely a bad thing, tariffs are not necessarily the right tool for the job, at least not alone. Tariffs alone will not fix all of the stated goals of “taking back our economic sovereignty,” “reprioritizing U.S. manufacturing,” and “addressing trade imbalances.”

The pausing of the majority of this tariff policy today (quite annoyingly after I already hit publish) reinforces the current instability of the market. President Trump commented about buying today ahead of the announcement, and some significant trade occurred prior to the market rebound today, causing Senator Adam Schiff to call for an insider trading investigation to be opened. It is important to say: if the President is inventing tariffs to create market instability for the purpose of making him and those around him richer, then the President is missing the point of the office that he was elected to.

So how do we change this?

I had written a paragraph here today that was unfortunately prescient4 that I preserved in the footnotes. These tariffs and the repealing/pausing of these tariffs are creating high amounts of market volatility that is not conducive to conducting business. Changing policy this significant on a whim is also not productive for America’s diplomatic interests, as other countries lose trust. As far as I am aware, the only ways that this could be beneficial for America’s interests are to “look strong” or to benefit traders. Neither offsets the issues presented by flippant policy.

The most straightforward answer to market uncetainty is for business leaders to ask for predictability, so that they can invest company assets appropriately. Many of them are already doing this, but there needs to be more publicly-visible alignment on the matter. Consumers of these businesses can put pressure on companies via their spending and saving habits, and shareholders can apply similar pressure in shareholder meetings when appropriate. All of these should happen to return certainty to the economy.

Assuming that these tariffs continue as they are slated to, companies will raise prices despite being told not to, and the public backlash to any cost-of-living crises needs to be severe to affect any change. April 5th was one of the largest organized protests against the current administration across the nation, despite receiving comparably less media attention than what it may have deserved considering at least tens of thousands of people took to the streets. This will likely be dwarfed in size by the crowds drawn if families are less able to buy groceries or other necessary goods because of the tariffs, and they will need to be that size. American attention needs to be on the plight of the working-class American and needs to be maintained there for change to occur.

When people discuss tariffs as being a tax on the consumer, this is what they are referring to. Businesses will tend to pass the additional cost onto the consumer.

When people discuss tariffs having an inflationary effect, this is what they are referring to. If prices raise due to tariffs, they are also unlikely to come back down if the tariffs are repealed.

I dislike the term “unskilled,” as I feel it undervalues how much effort goes into on-the-job training. While most people could in theory do the job as written coming “off the street,” being actually productive in that role takes time and practice in any “unskilled” labor role.

Well, for those wanting stability in the market, repealing the tariffs or again delaying them triggers more uncertainty in the market. Truthfully, the administration should have a plan and commit to it rather than changing it seemingly on whims. Even if the tariffs would be exclusively bad policy, business would largely be able to deal with it and rebound if the policy was enacted in a predictable fashion. This is not very predictable. I believe that most businesses who do business in America, whenever President Donald Trump was elected, did not actually expect mass tariffs to be the policy that stuck from the campaign trail, but here we are. As the retaliatory tariffs are meant to go into full force today, we will see if anything changes.

While I edit this piece from today's changes (which I expected may happen), keep in mind again that this sort of volatility is very bad for both businesses and consumers.