Educating for a World That No Longer Exists

The State of Computer Science and its Labor

I recall one spring morning at my local university, while I was pursuing my computer science undergraduate degree, the sights of white-painted cinder block, the smells of aged paper and tattered leather, and the sounds of a sort of aimless speculation. I had just finished discussing electives with my academic advisor to find myself in a conversation that I had no strong feelings about at the time. What would life look like in an age of artificial intelligence? Is it possible? Is it likely? We and many like us have been discussing it for nearly 50 years already, will it even happen in our lifetimes? What are the practical implications? In truth, I forget many of the non-practical details of that conversation, but I remember one intrepid young student’s opinion well: that programmers will always be safe from the potential ills of artificial intelligence, and maybe anyone who works as an artist, too, as an afterthought.

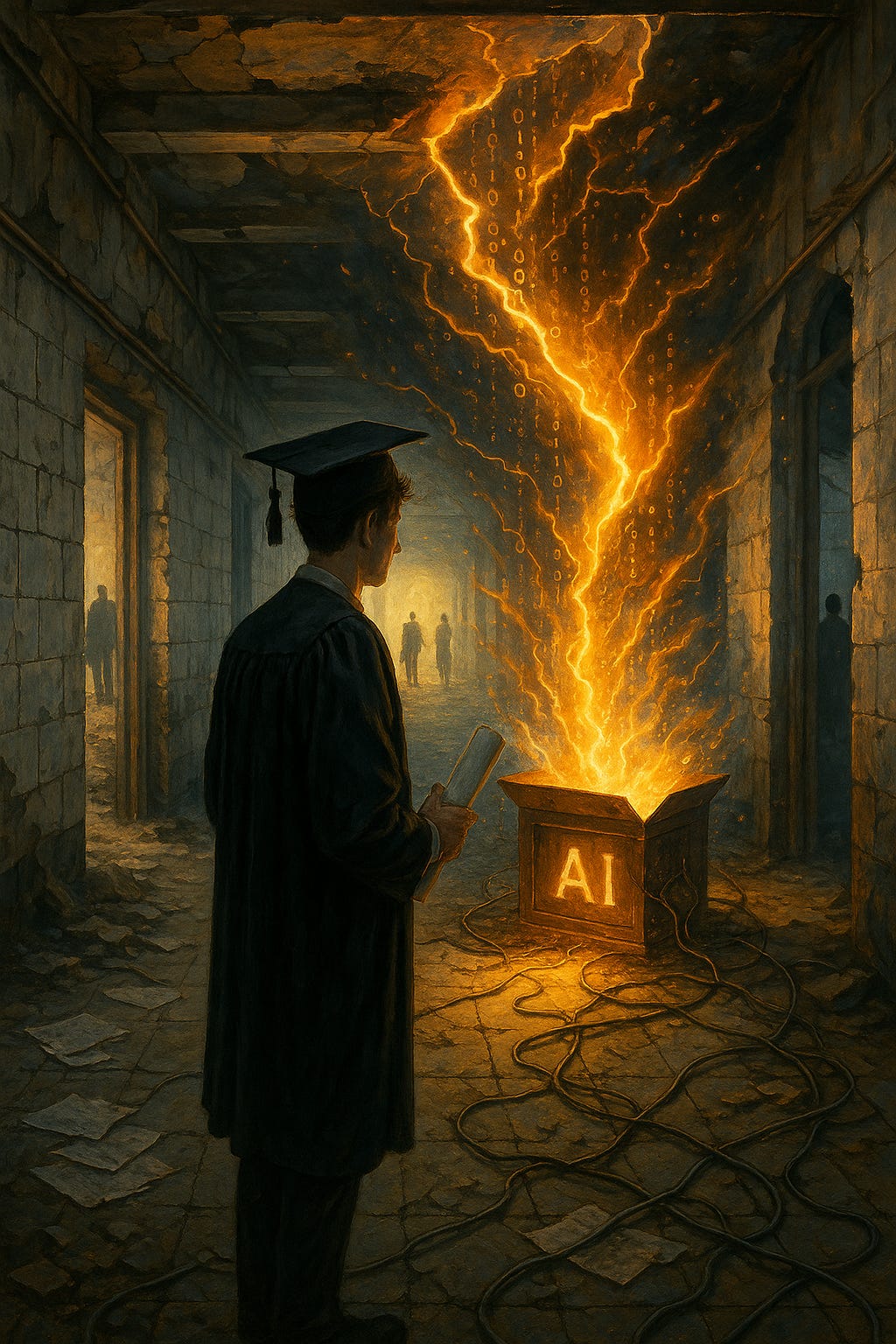

I use that anecdote often in my professional life to explain how unprepared people in the field were for the current wave of generative artificial intelligence. Even companies studying AI possibilities in detail, like Google and Microsoft, were caught completely off guard by how quickly it advanced. I feel that at a time when we were already struggling societally to deal with issues surrounding data privacy globally and the generational consequences of social media, that AI is Pandora's box. I find that these previous issues are still unsatisfactorily addressed. Even GDPR feels a bit too new still, as despite being a widely recognized standard when it went into effect in 2018, it is far from a global agreement. With the box being opened, AI has complicated existing problems while also creating brand new ones, including on issues of data privacy.

This will get worse as the technology gets better. For some disciplines, the labor pipeline needs rethinking now, not in 10 years as market forces shift. Take computer programming, software engineering, coding. The traditional pipeline for years has already been misaligned—a three-to-four-year bachelor’s degree in computer science with two years of experience only nets an entry level job. Becoming a standout applicant to land a job to just get those two “safety” years of experience was a harsh rite of passage for so long and now it is even harsher. Employment rates in the field, at least since the Great Recession in 2009, followed short-term business cycles that were predictable. Past the blanket COVID hiring freeze a decade later, and the job market has not rebounded in that predictable way, partly due to the uptick in AI usage in late 2022. The pipeline as we knew it is now fully broken, and we are largely not discussing that with students and prospects.

Every educator now needs to have an opinion about generative AI. The teaching profession as a whole, however, does not make enough money to be the stopgap solution for a worldwide shift in learning. The world was not prepared for these post-COVID shocks to the labor market, yet at a time of rising global income inequality, AI does not invalidate the work of multi-billionaires but does invalidate the work of many white collar workers. More and more computer science students are graduating at a time when junior roles are less frequently available, and this will affect businesses. Companies want senior roles filled now, but this is short-sighted if fewer seniors are currently being made. Businesses may not understand this fully right now, but chasing AI’s productivity gains in the short-term means potentially losing out on labor in the long-term. The latest “vibe coding” craze (that is, programming using AI without prior experience in programming) cannot hope to claim to fill this knowledge gap. If AI fails to capture what senior roles are capable of in the timeframe stated by AI leaders (2030 by many estimates), the labor market will be a mess for both those hiring and those looking to get hired. That is an awful lot of faith to put in a science that showed few productivity gains for around 60 years.

Unlike over a decade ago when I conversed with my cohort, I now have a firm opinion on the topic. There is no going back, obviously. Pandora’s box is open. Many have discussed the benefits that AI will bring, but few describe what the post-AI world looks like and even fewer describe the path to getting there. And of those possibilities, which future does AI enable? I am fascinated by AI and in turn afraid that we are blindly running off a cliff that will make hard skills even harder to learn and replicate in humans. I worry for the last few batches of computer science cohorts, much more so than I did for my own. That is all to say, I believe that artificial intelligence is a genuinely wonderful tool that humanity is wholly unprepared for, and that computer science educators and businesses alike need to look past their quarterly reports and evaluate if the industry is going in the right direction.

As a final word, I believe that the answer requires reevaluation of the computer science discipline. While computer science is a remarkable field, very very few computer science jobs exist. What actually exists are software engineering jobs. My recommendation is for a separation of degrees. Keep computer science as the specific “how does the science actually work” degree, but branch off a new degree that contains what graduates actually need for getting a job in software engineering. Maybe this looks more like a trade school program, but whatever the case may be, it should be founded in projects that students can put their names to on a résumé or a CV. Optimally, this could look like local and regional partnerships with businesses: building the students’ professional networks while developing real products for real businesses. Until we see a major shift in how computer science education is conducted, there will continue to be a broad disconnect between what academic instiutions offer and what businesses want out of an employee.

This is a shorter one—I've been working on a longer piece for quite some time and wanted to put something out there in the meantime. I had been canvassing this particular piece as an op-ed, but it's losing it's timeliness and so I thought it made sense to post it here. Thanks for reading!

I agree with your observation about computer science vs software engineering. Very few people today have experience designing an operating system or a compiler or a new processor. It was a wider field for tech innovation in the 1980s-2000s. Once the MBAs got a stranglehold on startup and investment, those opportunities for growth were stymied. But the mainstreaming of these technologies also means other fields require these skills, from healthcare to aerospace to manufacturing. So look outward.